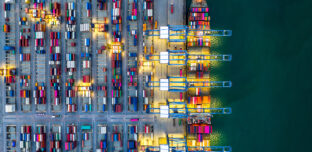

Maritime shipping routes are the vital arteries of today’s interconnected global economy, accounting for 90% of the world’s trade which is valued at more than $14 trillion.

The ever-improving efficiency of maritime logistics has certainly made goods cheaper – the cost of transporting an apple from New Zealand to Europe has been estimated at only eight cents – but the environmental price paid has often been ignored.

Shipping is responsible for 2.6% of all global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, or 714 million tonnes per annum, while vessels pump out 30% of nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, which have been linked to 75,000 premature deaths in Europe alone.

In the days of high sulphur fuels, one day of steaming from a large container vessel would produce as much sulphur oxide (SOx), linked to acid rain, as 53 million cars in one year. The east coast of Asia saw 400,000 premature deaths per annum from high sulphur levels. Although sulphur content has been regulated, it is still much higher than if LNG was used.

“If it was a country, shipping would be the sixth largest polluter on the planet,” says Nick Bentley, director – technology and innovation at BE&R Consulting. “However, to decarbonise the global fleet completely and use zero carbon fuels will cost around $2 trillion, including upgrading infrastructure.”

BE&R argues the immediate answer to this ecological and health time bomb is to power the merchant fleet with liquefied natural gas (LNG), a clear and non-toxic liquid which forms when natural gas is cooled to minus 162ºC.

The consultants predict widespread adoption of LNG in the new generation of ships just about to be commissioned could result in a 30% reduction in emissions.

It is an argument that has many detractors, not least the World Bank which disputes the emission-reduction argument and says adoption by shipping companies and port owners will be an expensive diversion on technology that will be obsolete by 2030.

Perhaps most importantly, it is incompatible with the Bank’s own preferred options for powering future vessels: ammonia and hydrogen.

Green ammonia, the type best suited to powering ships, is produced by a process of hydrogen electrolysis and produces zero emissions. However, it is 3.5 times more expensive to generate than brown ammonia, which is generated from hydrocarbons.

BE&R’s Nick Bentley does not dispute that green ammonia offers the promise of significant future benefits but contends they will not be commercially viable for the next generation of container ships and bulk carriers being ordered over the next five years. He believes the situation will have improved greatly by the time those vessels come to be decommissioned a quarter of a century from now.

“LNG is readily available, ammonia is only available as a fertiliser just now,” he says. “If we used LNG for the current super cycle of shipbuilding that is really going to help the emissions situation over the next 20 years. Once proven hydrogen/ammonia technology is available then we can roll it out at that point.

“The good news is that the majority of LNG bunkering infrastructure, where fuel is stored onshore, can be ‘ammonia ready’ with minor upgrades.”

In a detailed analysis of the competing claims for Moore Intelligence, Bentley says: “The World Bank was suggesting 5% of the fuel to power the world’s shipping fleet should come from green ammonia by 2030. That is 60 gigawatts of energy, so we are going to need a huge increase in the number of hydrogen electrolysers to produce this fuel.

“In reality, we are predicted to add 1.5 gigawatts per year, so by 2030 we might be lucky if we have 12 gigawatts on stream by then. This is still well short of where we need to be to meet commitments, not just in shipping but across the board.

“The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) has said we need to be able to produce 270 gigawatts of green ammonia by that point to put us on that trajectory to keep temperature rises to below 2°C.”

The direction the shipping industry goes on LNG will make a huge impact on countries with huge reserves of gas.

“Qatar is very well placed in LNG as it is good quality and light,” says Sami Zaitoon, Managing Partner at Moore Qatar. “They are currently producing 70-80 million metric tonnes and planning to increase that to 130 million metric tonnes by 2027. That is the equivalent of 6-7 million barrels of oil a day.

“The country’s objective is to lead the world in the supply of LNG. In the next 30 years they are trying to invest in the entire chain from downstream to logistics, from storage to transportation. I see LNG helping to produce a very good cash surplus for the country.”

Discoveries in Mozambique suggest the southern Africa country could be at least as important in the development of LNG as Qatar.

A terrorist insurgency has forced French major Total to rethink its construction timetable for its Mozambique LNG operations and remove all staff from the site on the Afungi Peninsula. However, it is estimated the fields could earn the country $100 billion over the next 25 years when completed – six times its current budget.

“Last year in that small corner of Africa there was the highest concentration of engineers on the planet,” says Olivier Barbeau, Managing Partner at Moore Johannesburg. “In the town of Pemba there were city planners that had been seconded there from Aberdeen Council saying, ‘If what happened with us happens here, you have to build infrastructure’.

“However, Mozambique’s fields are many multiples bigger than those in the North Sea: it will be the biggest gas field on the planet.”

Getting the gas out of the ground is not the only obstacle facing supporters of LNG as the fuel of choice for shipping, at least in the short- to medium-term. The quayside infrastructure is well established in Europe but haphazard elsewhere.

“LNG bunkering is a key part of the puzzle but it is not cheap to implement,” says David Tomasi, Global Leader of Energy, Mining and Renewables at Moore Global. “However, we are hopeful the story around LNG as a practical and more environmentally-friendly marine fuel is starting to resonate.”