By Dr Peter Matanle

Gender and generational dynamics are key factors in the implementation of successful ESG strategies but are often overlooked in the debate about the impact companies have on the environment and their governance structures.

We have been studying South Korea as it has evolved into one of the world’s leading economies. While it is at the cutting edge of technology, there are growing social tensions behind the scenes as more highly educated women enter the workforce and are not prepared to accept the old norms of male domination in corporate hierarchies.

It is a clash between traditional values and modern aspiration that will ultimately be repeated across the whole of East Asia, the centre of global manufacturing. There are also echoes of what companies in the US and Europe have been wrestling with for the last four decades.

South Korean companies tell us in interviews about a wide gap in attitudes and values between different generations in their workforce. This hinders effective communication between management and employees and may underlie sub-optimal decision-making on hiring, promotion and leadership.

This is potentially important for business performance over the long term. So, me and my team at Sheffield University in the UK set about trying to understand the underlying causes and their possible outcomes for companies.

South Korea’s generation gap is particularly evident in – indeed caused by – significant rises in educational attainment levels. While only 27% of South Koreans aged 55-64 achieved tertiary education, the figure for those aged 25-34 is almost 70% for, a 42 percentage points increase in a generation.

The pace and scale of change in South Korea is particularly noteworthy and presents the biggest jump among all OECD countries. Even in Japan, often compared to South Korea due to similar socio-economic development trajectories, the generational achievement gap in tertiary education is less pronounced.

This disparity is sure to produce impacts within organisations as different generations of management and employees try to work together harmoniously and productively.

South Korea also exhibits a dramatic gender shift in educational attainment. Historically, men outperformed women in education, with 35% of males aged 55-64 today holding tertiary qualifications compared to 20% of females. However, this trend has reversed, with 76% of women aged 25-34 achieving tertiary education, significantly outpacing their male counterparts at 63%.

This increase in female educational attainment is the highest among OECD countries, signalling a profound shift towards gender parity in education overall.

GROWING GENDER WAGE GAP

East Asia has yet to adjust itself structurally and practically to these emerging gaps. Despite educational advances, highly educated South Korean women face significant wage gaps once they enter the workforce. Japan, once more, is similar though less pronounced.

The gender wage gap in South Korea stands at a staggering 31.2% – the widest among OECD countries. This gap suggests that although South Korean women are among the best-educated globally, their skills and talents remain under recognised and undervalued in the workplace.

Legal frameworks like the Equal Employment Opportunity and Labour Standards Acts are in place to ensure equal pay for equal work. However, the persistent wage gap is a symptom of deeper structural issues.

Women often bear the brunt of unpaid domestic responsibilities, such as childcare, which limits their ability to respond to companies’ demands for employees to work long hours, respond to overtime demands or participate in work-related social events. These requirements are culturally embedded within organisations and were developed at a time when employees and managers were predominantly male.

Consequently, it’s hard for women to maintain continuous, meaning unbroken, employment and companies are therefore more reluctant to invest in the development of their female workers.

This creates a circular and cumulative disadvantage for women, leading to fewer career advancement opportunities and lower wages over time. The outcome is a widening achievement and earnings gap between men and women as people get older, despite the fact that, on the whole, women are now better educated than men.

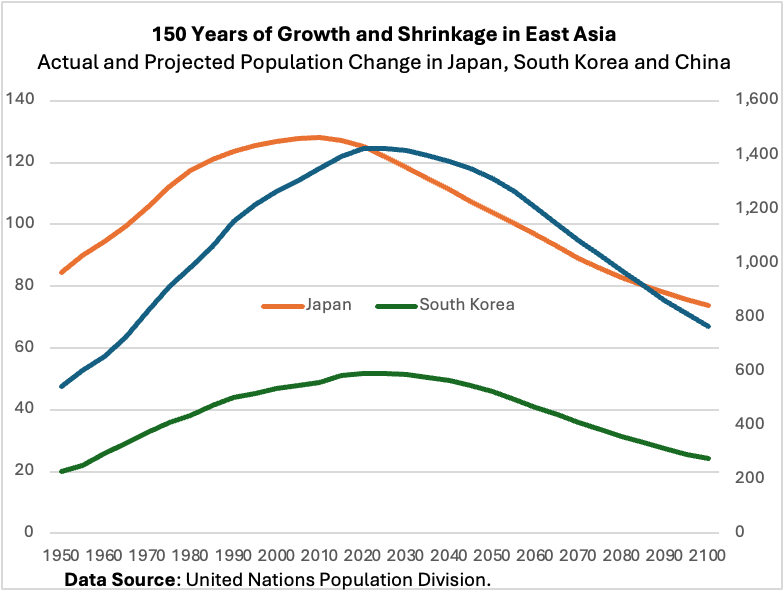

Like Japan, South Korea faces significant demographic challenges that compound these gender and generational issues. It has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world, at 0.72 children per woman in 2023, far below the replacement level of 2.1.

This has resulted in a shrinking and ageing population, putting immense pressure on the labour force and the economy. By 2050, nearly 40% of South Korea’s population will be aged 65 or older, making it one of the oldest societies in the world.

By then, all East Asian populations will not only be ageing, but they will also be shrinking.

These demographic trends necessitate a rethinking of workforce strategies to ensure sustainability. With fewer younger people entering the workforce, South Korea cannot afford to underutilise any segment of its workforce.

Japan has made strides in increasing female labour force participation, and South Korea needs to follow suit to maintain its competitive edge. Indeed, ensuring that women can pursue careers without facing systemic barriers, is not just a gender equity issue but a national economic imperative.

VALUING THE ‘SOCIAL’ ASPECT OF ESG

While diversity is a critical component of a progressive and innovative organisation, it is crucial to recognise that diversity without inclusion amounts to tokenism and will not yield the desired benefits for companies’ bottom lines. It can also cause resentment and even harm overall performance.

Research consistently shows that diversity alone is insufficient to drive organisational performance. Inclusion, which involves creating an environment where all employees feel valued, respected and empowered to contribute, is essential for innovation and creativity to flourish.

In short, it means equalising the opportunities to which men and women have access. However, this doesn’t mean asking women to work like men. That is impossible and, again, is likely to cause resentment and increase costs. To get the best out of their workforces, companies need to offer pathways to excellence and progression that suit the diversity of their employees.

We found in our quantitative research that companies which hire more female permanent staff and reduced their reliance on temporary contractual workers performed better financially over the long term. There are a lot of good reasons why this might be so but it points to the benefits of a properly inclusive rather than merely a diverse workplace.

However, we also found that with diversity and inclusion comes complexity in managing operations and companies need to be careful not to lose the gains they get from inclusion by spending more on coping with complexity.

We believe that employment standards and practices – the S in ESG – are the foundation stone for the whole ESG framework. Without talented and committed employees, companies will find it harder to implement and derive value from high performance environmental and governance standards.

By leveraging the educational advancements of its younger generations and addressing structural barriers, South Korea can build an even more inclusive and dynamic economy.

By fostering a workforce that is diverse, inclusive, and well-utilised, South Korea can ensure long-term growth and stability in an increasingly competitive global market. Equality is not just good for women; it is essential for the prosperity of the entire society.

East Asia remains the most dynamic area of the world economically. However, there are significant challenges to be faced by all countries in the region – especially South Korea, Japan, China, and Taiwan – as they develop further.

The intersection of gender and generational divides with a demographic slowdown is possibly the most significant challenge for companies to manage successfully. If East Asian businesses can transform their employment practices and principles, they can unleash a new wave of growth across the region.

Dr Peter Matanle is senior lecturer at the School of East Asian Studies at the University of Sheffield. Research team also included Yejin Shin, Yang Li and Zhamayne Fakhurazi