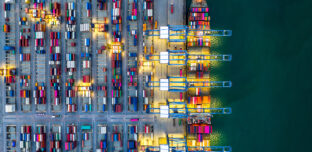

Real Estate & Construction

The commercial and industrial real estate and construction sectors are ever changing. Operating within a constantly shifting landscape of market dynamics and regulatory changes, businesses within this sector need support from a partner who truly understands the market.

From commercial and industrial developments to residential projects, success in the real estate and construction sector requires businesses to juggle the complexities while staying ahead of emerging market trends.

Our member firms have extensive experience and deep knowledge of this sector, which means that we understand that every business is unique.

We get to know your business inside out, delivering the highest quality service whether your needs are local, national or international. From tracking investment flows to providing tailored tax solutions, we’ll support you with both your regulatory and commercial needs in mind.

Our areas of expertise include project planning and cash flow forecasting, research and development tax relief, employment law and taxes and outsourced accounting services. Whatever your needs, when you work with us, we’ll help you to rethink the traditional paths to successful investment, while maintaining focus on the opportunities of tomorrow.

Our Specialists

Intelligence

Downloads/Materials

Downloads/Materials

Contact Moore’s global experts

Our Real Estate and Construction professionals are dedicated to understanding your unique challenges and turning opportunities into lasting impact.

- Contact Us

- Proposal Request

- Join Moore

"*" indicates required fields

"*" indicates required fields